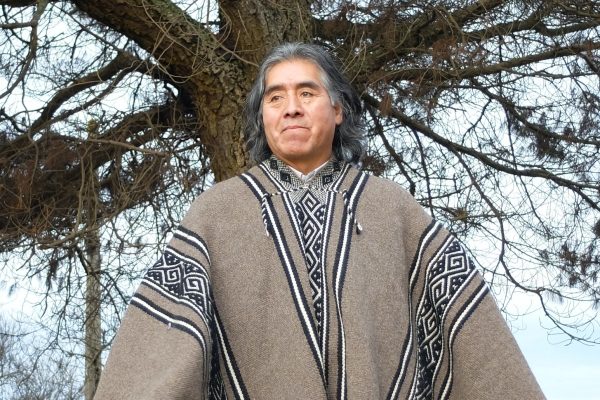

Well, my name is José Naín Pérez. I am Mapuche from the commune of Galvarino. We are now here in this place, my community, Pangueco Soto Lincoñir. This is northwest of the city of Galvarino, about 14, 15 kilometers. And we are in a very symbolic place for us, for the Mapuche who live in this place. Here there are about 14 Mapuche communities that we began to gather during the military dictatorship. Our longkos, our machis, our leaders, our werkenes of the time began to raise the movement that became known at the national level, which was called Admapu, which was a Mapuche organization at the national level, where there were many Mapuche leaders from the region. There were also people from Santiago. But what I remember is that this movement was created to raise the demand for social justice, but also to influence what it meant to seek justice for the people who had been detained and disappeared. For the tortured Mapuche there were many people who came to this place and who were from families that had disappeared. Mapuche from Lautaro, mainly from Galvarino. Mapuche from Lumaco, I remember. I also remember that there were people from Panguipulli, who came and who wanted to seek justice through this Mapuche collective movement. It was very difficult because we all know the connotation of the military coup in Chile, one of the strongest dictatorships in America. And that undoubtedly meant for us the numbness, the loss of many things that were part of our culture. Because Pinochet dictated a law that said that the indigenous lands ceased to be indigenous and that those who inhabited them were no longer indigenous. That is to say, Pinochet wanted to eliminate us by a decree law. It was not possible, they divided the lands, yes they divided them, but we did not cease to be Mapuche. They did not take away our idiosyncrasy, they did not take away our language, they could not take away our culture, our spirituality. And with that we are still connected to the land. And these elements also made it possible for the Mapuche to raise this movement inspired in our culture, in our spirituality, in our religiosity, to mimic what was the Mapuche political project that was coming with great force, that was emerging in different regions, in different communes of the country. And one of the important acts of this organization was precisely in this place, in Pangueco. Others were also held in Lumaco, in the community of Collinque. They also took place in the community of Panguipulli, in Lautaro. But this was undoubtedly one of the largest because of what it meant to live in the center of the Mapuche territory. Many, many Mapuche forces converged here. Many longkos, many machi, many authorities. I remember that we were always surrounded by the military. The military came to ask what was going on in this place. And our elders, our longkos, our leaders would tell them we were performing a spiritual ceremony. Spiritual that we always do, that we do from time to time and that has nothing to do with politics or anything else. The astuteness that they had today, I can remember it very strongly because it was an activity that was against what Pinochet dictated. That people could not gather, that they could not meet, that they could not carry out political or cultural activities by law. However, we were able to do it. And from here we began to plan the first land recoveries. The first land recuperations were made from here. The movement arose and the land began to be occupied. And it was also all very clandestine, to say it today. But it also meant that we wanted to take possession, we, I say, because I am also speaking on behalf of my ancestors and of the people who are still alive today. We also wanted the people of Chile to know that despite being with them in the pain of the military dictatorship, we also wanted Chileans to see us as a different people. As a people that had our particularities and that those particularities made the struggle also be in a different way. Because we not only lost our loved ones in the military dictatorship but we also lost the land. We lost the land, this land that was given free of charge to forestry companies, foreign and national. So a lot of land was taken away from us. So it was a double blow that had been dealt to us, to the Mapuche, and we also wanted the Chileans to understand that and that if a small window was opened, as was the plebiscite, our particularity would also be considered. That was the aim, it was not only to fight against the military dictatorship but also to fight against that bias that Chilean society often had or still has and that many times they say that we want privilege in this country. We, the Mapuche, do not want privilege in this country. The Mapuche were the first inhabitants of this land. We are the natural owners of this territory and today we are the poorest, the most dispossessed, the most isolated and I think that is what we were looking for and that is also why from our communities, from our territories we supported the plebiscite.

We raised our cultural flags that we had at that time because we did not have a unique symbol, we had the white flag, the blue flag, each community had its own flag and we went out with our flags to fight against the military dictatorship. And the Mapuche did participate in the plebiscite and how did we participate in the plebiscite? First in a struggle for the plebiscite to be held to raise awareness among our people, but later we also participated by voting, voting and I remember that here there were caravans of people who went to vote. Many, many Mapuche were intercepted in the streets by the military telling them to vote for Yes, to vote for Pinochet, that the dictatorship was going to solve their problems, but the people did not believe in these things anymore. And the Mapuche movement began to rise like a snowball and began to empower itself. And I believe that this was what filled us with a lot of strength for the generations that were coming, because this Mapuche political-social movement also led us to strengthen our identity. It came to tell us that the real struggle that we had to give as Mapuche had to be with our identity, not to go over to the Chilean side, because by going over to the Chilean side we would lose everything we had or what we had as a people. So for us in the collective memory of the Mapuche it is that we supported Chilean society a lot to get out of the military dictatorship. We took a gamble. There were many Mapuche leaders who took a gamble. Many Mapuche leaders went into exile.

Many Mapuche leaders who died. That was our contribution to the resistance against the military dictatorship. But when this whole process of change was generated to get rid of Pinochet, and for Pinochet to leave and for the famous democracy to arrive, the center-left political parties also forgot about us, they forgot about the Mapuche people. They began to make politics with their militant friends who were of Mapuche origin and that is when it began to become distorted. And at that moment we, the ADMAPU 87, 86, 87 movement was already in decline because it had become politicized. The left-wing political parties and ADMAPU got involved at that time. I remember that they began to make it look bad. The internal division began and a faction of ADMAPU said, we are leaving.

And we looked at our communities and thought, why don’t we take that strength from the cultural centers, from the cultural events we did in the different territories to help get rid of Pinochet and turn it into a social political movement? And in 1989 what was also known as the Council of All Lands (Consejo de Todas las Tierras) emerged. It was formed under the wing of the longkos, the machis, the wewpifes, the ngenpin(es) who are the political, spiritual and religious figures of our people. And there we anchored everything that was our political demand and we began to generate what we wanted to do with the Council of All Lands. We first wanted to demonstrate to the political class that was taking control of the government in Chile that we wanted our rights to walk a totally different path from the demand that Chile had as a society. That there was a debt with the Mapuche people, that there was usurped land, that there were rights that had been violated in this country, and that it was a good way to begin to look for a solution, and within the milestone that we set was the commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the Spaniards in America. The 500 years was a very symbolic date for the indigenous people of America and the Mapuche were part of that. And we proposed to raise a Mapuche symbol as if it were a flag. We began to discuss the fact that we do not have a symbol that identifies us. We cannot speak in the media…when the Mapuche mobilization came out, the media always put a little screen in the back, there, when you watch TV then they talk about soccer and they put something…and when they talk about the Mapuche they didn’t know what to put, whether to put a woman dressed as a Mapuche or a Mapuche with a hat. We began to realize that we needed the world to know us through a symbol and that symbol for us was the flag. It was all very complex because at that time there was perhaps no technology and no means of mobilization. We had to get to Neuquén, we had to get to Bariloche, we had to be in Zapala in the Argentine territory, but we also had to get to Chiloé, we had to get to Santiago, from the Cordillera to the sea to consult and involve all the communities and all the Mapuche who wanted to build this political project of the Mapuche flag. The people were very motivated and very supportive. The Lafkenche made their flag, the Pewenche made their flag, the Wenteche, the Nagche, the Puelche of Argentina and then we synthesized because the colors were similar for us, the colors are well defined. For the Mapuche, blue is always infinity, space, clarity, hope, luminosity. There was blue. There was green, green represents biodiversity, the itrofill mongen, we say. Medicine, life. There was yellow, which represents the kultrun, which is the figure of our symbol that the machi uses to heal. And of course the red, which is not the best, but which is also a symbol of the fact that Mapuche blood has been spilled in this territory for more than 500 years. Since the arrival of the Spaniards until today there have been young people who have been killed in democracy by the police. And all of this has stopped decanting. The land continues to be stained with Mapuche blood when it should no longer happen. Because one says well, human rights violations were atrocious during the military dictatorship but in democracy we have already had around 14 young people murdered at the hands of the police, agents of the State. So, be careful with the violation of human rights in the Mapuche case, yes, well, so we built this flag project, we took out the unique flag and on October 6, October 6, 1992, we launched the flag in Temuco with about 1500 people. We made a very big edition of the flag and we gave away the flags and everything and that same day, under the former president Aylwin filed a lawsuit against our organization for association with the Mapuche people.

And they prosecuted us, they condemned us, they began to ask us to lower the flag and not to raise that flag anymore. And we had to begin to explain to the political class of Chile, to the Chileans, to the political class of the center and the left that we did not want to invade anyone, that the Mapuche flag was not to impose it on anyone, that it was not a bellicose flag that only had the purpose that we the Mapuche had a symbol that identified us. And whoever felt Mapuche in his heart and mind should embrace that flag and whoever felt Chilean being Mapuche should continue to embrace the Chilean flag. Because for me and for many at that time the Chilean flag was the flag that had usurped our Mapuche territory. Once they conquered this territory under military violence the first thing they did was to put up the Chilean flag. So for me that was not an act of recognition and there we had the flag. The 144 Mapuche were sentenced to three years and one day in jail, some of them escaped with another type of sentence, but it became a very important milestone in democracy that the repression continued with us. Then this movement continued, of course we continued working, we continued doing very big cultural events because we continued using in the good sense of the word our culture, our cultural expressions to generate the Mapuche movement to strengthen it to fight against the forestry, against the colonists who had usurped our lands. So this that is here, this that you came to see. It is like the floor, the anchor, it is the basis of everything that today the Mapuche people have built after the plebiscite, after the military dictatorship, with recovered lands with scholarships for the indigenous children who are studying, with many more facilities with the delivery of legal land from the State. But everything was born here around a rewe that is no longer here, that was burned. But those of us who still have the conscience as a people, as a collective, we will continue to have it, we will continue to use it. We are going to continue trying to show our children, our young people that the land is important and the land is the best witness we have of how we have suffered, but also how we fought to conquer our rights.

Interview conducted in July 2023