Well, on the day of the plebiscite. Well, you know that I work in editorial drawing, making comments on current events, not necessarily political, but related to reality, let’s say. That day I went to work for the magazine. I actually invented the job because there were photographers and journalists, but I told them, “Look, if you want a drawing, I have to be involved, so give me a super credential that allows me to move around everywhere and I want to snoop around everything.” They gave me that credential, so I walked around different places.

In between, I went to vote. Voting was quite exciting because I was assigned to a table where I had friends, so it was like, “Now we’re really screwing this guy over.” And I spent the day watching the voting process. The people were incredible, full of hope. There was a sense of camaraderie that has never been seen again here. So, whether you were an anarchist, a communist, a right-wing democrat, everyone had to get rid of this beast. Well, that feeling is very beautiful, very pleasant. It uplifts your spirits. I voted and then I went to visit the polling stations, and you could see that feeling everywhere. The opposition, or at least the parties against the dictatorship, had organized themselves for a parallel count. It was very organized. The entire country had mobilized to create a group, which is not easy. There was also a large central computer that engineers had dedicated themselves to setting up. It was like NASA, you couldn’t enter, you couldn’t touch anything. They were counting everything electronically there. It was heavily guarded because there was concern that there could be an attack on that place to prevent us from having that technology. And it was probably advised by volunteers from other places as well.

Well, after voting, I went to the Diego Portales building to wait for the official results from the dictatorship. I witnessed the delays and delays there. There was great anticipation, and we were discussing it with the journalists, saying, “Hey, this is strange, maybe they are unaware of some result. Another coup might come.” I would say, “No, how can you even think that? It would be the ultimate discredit. They have everyone watching them to prevent this.” And we joked, saying, “Either the Soviet Union or the United States will invade us because this just can’t be!” Then the official count was announced: celebration, carnival. People took to the streets. And there I was, blending my work with being just another citizen celebrating. There were beautiful things happening, like the camaraderie I mentioned earlier, people embracing each other… Champagne was flowing in the streets, everything.

You know that Plaza Italia is the center of sports and political victories, and the Alameda, nearby, in front of Diego Portales, was the command center for the NO campaign. The elite entered there, and I wanted to go see the elite. But a guy stopped me at the door. He was a politician who had spent almost the entire dictatorship in New York. He asked, “Who are you? What are you doing here?” I said, “I’m going in to see things,” and all that. He replied, “No, only people with a special credential can enter.” I knew his history. I told him, “Look, we risked much more than you did, so don’t give me any crap.” The guy insisted and wouldn’t let me in, and then some ridiculous bodyguards came out. It was like the dark side, and you could already see the owners of the victory emerging, you know? Luckily, the number two of the command happened to pass by in the hallway, and he said, “Guillo,” and I said, “Mariano, these guys won’t let me in.” So he said, “Come in, my friend.” Well, I argued with the guy and finally got inside to see the other side. That’s when the politicians started arriving. It was the moment when everyone jumped on the bandwagon. They hopped on and climbed aboard. The politicians started arriving, each with an anecdote linking them to the victory, and I took note of it all. Many artists also came, top-tier ones, who were friends with politicians and those from the theater, people with a history. But they didn’t come in there. Only the famous ones, the ones from television. I quickly left because seeing that gave me great disillusionment, but the sense of triumph I had witnessed among ordinary citizens was even stronger. I went to the Alameda to celebrate with the people. And I never thought that the feeling I experienced there would years later become the actual reality of what was going to happen.

For me, at that moment, all those politicians were trench fighters. Some more than others, but I respected them. After the coup, my party, which was the Mapu at that time, because of my technical skills, asked me, a 20-year-old, to create a kind of cell that forged documents because we thought they would be necessary if a coup occurred. And we learned it on our own, we didn’t go to any courses in Bulgaria, Cuba, or anywhere else. I gathered a group of friends from the art school, a photographer, a designer, and we set up everything. And because of that, when the coup came, I became very important to the parties, to that party, and to other people. I met many politicians who were escaping and needed to cross the border to Argentina. That put me in contact with the Olympus, you know? It’s quite difficult at the age of 20 to be on friendly terms with someone who is 40, but it helped me establish a network of gratitude. No, they didn’t catch any documents. That’s like the record, and people would leave through the Libertadores Pass to Argentina and through the airport. Well, with today’s technology, there wouldn’t be any results. But at that time, it was possible. And well, I saw some of those politicians inside. I met them with fear, they were scared. I was their only contact for weeks. I would update them almost daily; they relied on me. Well, and there I see those guys, empowered and already boasting. It bothered me a lot because I thought, why aren’t they celebrating outside? This place should be empty. It had fulfilled its role as a meeting place, but now they should be with the other people. All of this was based on sensations, not certainties, because I was fully committed to the cause, and we were all brothers and friends. But they were sensations, a mixture of good and bad. And later on, I began to see the face of the monster, those friends of mine who had become secretaries, chiefs of staff, ministers, holding important positions in the government, starting to become mentally corrupted. I didn’t know about the financial aspects yet, but mentally, you could see that they were preoccupied with other things rather than serving the people, which was the spirit that animated all of us.

I worked on the “No” campaign, specifically in the humor section. Ignacio Agüero, I don’t know if you’ve heard of him. Well, I would come up with ideas and give them to him. We made an animation with a little chick that broke out of an egg and started singing. Instead of “pio pio” (cheep cheep), it said “let’s say no,” and it was very successful. It provided gags for the actors. We also made one about tennis, where a guy played the character of Pinochet. He was dressed like a tennis player, you know, colorful or white outfits? Well, he was all dressed in black, with black glasses, and instead of sneakers, he wore boots. These were grotesque boots that tore up the clay court, and on the other side, there was a rooster representing the Chilean Tennis Federation. So, the guy served, and the line judge said, “No.” He served again, no, and he cheated and served like five times. No, it didn’t change. That was one of the gags I created. I never saw it; I don’t know what happened to it. But when they reviewed it creatively, they liked it a lot.

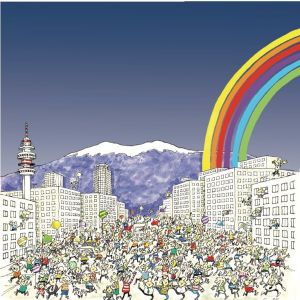

Well, that’s the whole story of the documents and the campaign. I’m telling you that these characters, whom I saw in all situations, diminished, inflated, and betraying many of them, not all but many of them, betrayed the spirit that animated all of this. And well, that was my day. Then I went back home, and it was a mixture of joy, hope, but with that bitter taste that I had witnessed, but didn’t fully understand yet. I made a drawing that was more like a photo-drawing. I remember drawing an idea that Gato Gamboa had. Do you know Gato Gamboa? He was the director of Clarín and Puro Chile, and Fortín Mapocho and he wrote, “He ran alone and came in second.” It was very good, and it made headlines the next day. So, I drew it because I thought it needed the force of the image. I drew the situation with Pinochet, there in second place on an empty podium. But I also drew the celebration on the street that I had seen on the Alameda. Those drawings were like the Sistine Chapel, with so many characters, like “Where’s Waldo?” And halfway through, you regret having that idea because it’s too much. At that time, there was no copy-paste to fill in spaces; I did it all by hand. But it was worth it. And next was the magazine. It was like Chile had won the World Cup; beer, conversations, and reminiscing. That generation of journalists was very brilliant. They were valuable people who have maintained the spirit, you see, it’s possible.